Of Bulls and Bears – Margin Impact from Changing Yield Curves

After the blog published on April 21, 2016, we have received a number of comments regarding why we were silent on the industry “conventional wisdom” that a wider yield curve can provide stronger net interest margin, and that a narrower yield curve can squeeze the margin. This can be true, but often is not. All else being equal, a wider yield curve would produce stronger margins. However, real life seldom results in an “all else being equal” outcome. Business, and the economic climate, are not static. There are constant changes to the regulatory, economic, and competitive landscape that can (and does) change consumer behavior – and the changes in consumer behavior result in changes and shifts in credit union financial structures.

Bear Flattener

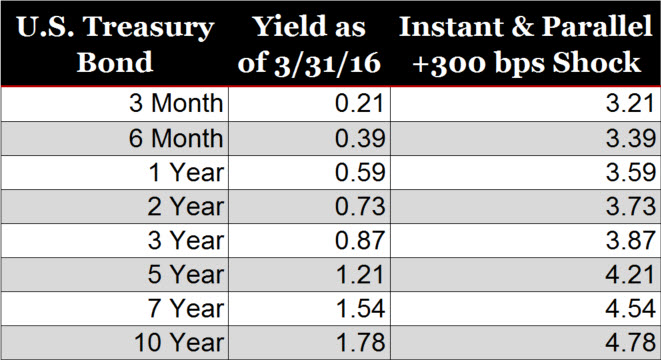

If we were to apply “conventional wisdom” to the most recent “bear flattener,” which occurred from 2004 to the end of 2005, real world results are not what would be expected. In June 2004, the industry net interest margin was 3.26%. In June 2006, the industry margin had barely moved down, reaching 3.20%. This barely quantifiable movement in margin happened when the yield curve moved from roughly 350 basis points (bps) to about 20 bps – a reduction in steepness by more than 300 bps.

Using the “all else being equal” argument, margins may have been squeezed more. However, there was a mitigating factor that helped to preserve the margin – the loan-to-asset ratio for the industry increased more than 5% over that same time frame. The increase in the loan-to-asset ratio helped to offset margin pressures that could have been realized if “all else being equal” loan demand had not increased.

Bear Steepener

Applying the same conventional wisdom to a recent “bear steepener,” which occurred from 2012 to 2013 long-term rates increased more than 100 bps, translating to a yield curve that is roughly 100 bps wider than it was December 2012. However, net interest margin for the industry dropped from 2.94% to 2.80%. Comparing the end of 2012 to the end of 2015, the yield curve has been consistently steeper and loan-to-asset ratios jumped 7% (to 65%), but the margin of 2.86% has not rebounded to the 2012 level.

Now, some may argue that there were so many other variables and moving pieces in the broader economic climate, “all else being equal” or using an “apples to apples” comparison, margins should have increased. That may be the case. The same arguments are brought up in relation to static income simulation. Breaking it down into the fundamental components, everyone realizes that real life isn’t static – things change, member demands and consumer behaviors shift, and the competitive landscape has a significant impact on credit union earnings and risk profiles. The entire reason for the thought that wider yield curves bring stronger margins is a lack of change in the composition of assets and liabilities in static income simulation. This is antiquated thinking that has resulted in potentially misleading “conventional wisdom.”

Conventional Wisdom can be Misleading

As an industry, we have seen yield curves widen (steepen) and yield curves narrow (flatten), loan-to-asset ratios increase and loan-to-asset ratios decrease, with inconclusive correlations between changes in the yield curve in relationship to actual bottom-line net interest margins. Credit union management teams, boards of directors, and even regulators should be concerned with an assumption of static replacement regardless of the change in the environment, as it is often misleading. For decades we have been modeling a huge range of yield curves and environments, and this experience has taught us the importance of modeling how members may respond differently in these environments. Additionally, it has demonstrated that better business decisions can be made by first understanding the potential profitability (or losses) from the existing structure, prior to layering on guesses about what the new business may be able to do in all of the different environments.