AICPA: Buzz About CECL

We had the benefit of speaking at the AICPA conference on one of our favorite topics, how to use ALM for actionable business intelligence. In this case, the focus was on how a credit union can support changes to remain relevant.

Another topic that also had a lot of buzz at the conference was CECL, which can also impact relevancy. Based on the discussions, we thought it would be a good idea to repost the blog from May 19, 2016.

CECL’s Threats To Your Business Model: Six Questions To Consider</font size>

CECL is a new set of rules that every credit union eventually will have to play by. While it may not be in effect until 2021, many credit unions could find that they need all that time to reposition their business models to prepare for its impact. Keep in mind that the impact being discussed currently is in a good credit environment. How does the exposure to CECL change in a bad credit environment?

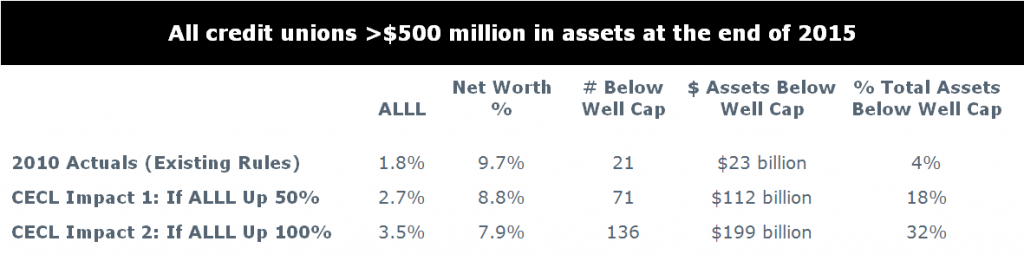

At the end of 2015, the nearly 500 credit unions with assets over $500 million had an average net worth ratio of 10.9% and an ALLL of 0.9%. If the impact of CECL causes ALLL to increase 50%, or even what some refer to as a worst case of 100%, the net worth will be reduced but not dramatically for most.

For those same credit unions, if you were to go back to the Great Recession, what potential impact could CECL have created?

While many experienced a reduction to ALLL in the years following, what would have happened to the credit unions that would have had materially lower net worth? How could this impact business models and strategic decisions going forward?

Every credit union should be asking:

- Because CECL will be extremely volatile in changing economic conditions, how much net worth do we need to have to prepare for that potential additional volatility?

- How should our business model be repositioned so that we have enough net worth in volatile, bad case scenarios?

- If our current target markets are susceptible to credit risk and could wipe out significant amounts of net worth under the new CECL rules, do we need to adjust who we target in the future?

- After CECL is in place, loan growth, especially strong loan growth, will come at much lower initial profitability. How does this impact our business model?

- What changes should we be making, if any, to our concentration risk policy?

- If the battle for prime paper increases materially, will we choose to increase our presence in that battlefield, and how will we differentiate ourselves in order to remain relevant?

If you don’t think these questions are relevant, consider that in today’s good credit environment, 22% of all existing auto loans are to subprime borrowers (Wall Street Journal). How much could this increase in a recession due to credit migration?

As you wrestle with the mechanics of implementing CECL, it is even more important to think about the business model implications. In addition to the current economic environment, think through what could happen in a recessionary environment when loan losses can mount rapidly and the impact of CECL can be magnified.

The point is not to dissuade you from taking credit risk, but rather to stress that the rules have changed; everyone will need to be much more deliberate with their business models, strategic plans, and the execution of those plans to be well-positioned for CECL.