Interest Rate Risk Policy Limits: One Big Misconception

We initially published the blog below on January 28, 2016. With interest rates having increased recently – and more increases seemingly on the horizon – we thought this a good topic to revisit as it has been coming up in model validations we complete.

We often see interest rate risk policy limits that rely too much on net interest income (NII) volatility and miss the absolute bottom-line exposure. Such reliance can cause boards and managements to unintentionally take on more risk than they intended. Why? Because these types of policy limits ignore strategy levers below the margin.

Establishing risk limits on only part of the financial structure is a common reason for why risks are not appropriately seen. Setting a risk limit focused on NII volatility does not consider the entire financial structure and can lead to unintended consequences.

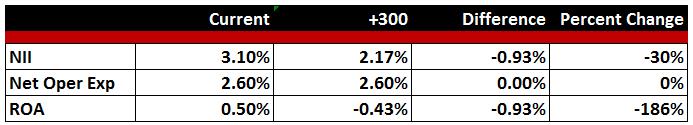

For example, assume a credit union has a 12-month NII volatility risk limit of -30% in a +300 environment. The table below outlines their current situation and the margin and ROA they would be approving, as defined by policy, in a +300 bp rate shock.

By definition, the credit union is still within policy from an NII perspective but because of the drop in NII, ROA has now decreased from a positive 0.50% to a negative 0.43%. This example helps demonstrate that stopping at the margin when defining risk limits can result in a false sense of security.

Not All 30% Declines are Created Equal

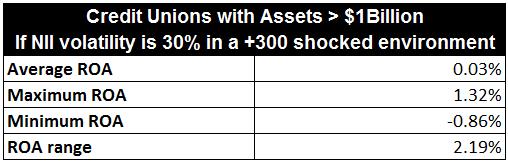

To punctuate the point, let’s apply the 30% volatility limit to credit unions over $1 billion in assets.

On average, if this group of credit unions experienced a 30% decline in NII in a +300 bp shock, the resulting ROA would be 3 bps.

But each credit union’s business model and strategy are unique. So instead of looking at the average for this group, let’s look at the potential range of outcomes.

It is important to note that 47% of all credit unions with assets over $1 billion would have a negative ROA within 12 months if this volatility were to occur.

This enormous range of ROA, and with so many credit unions at risk of negative earnings, helps demonstrate that an interest rate risk limit along these lines could result in material risk with the unintended consequence of institutions being potentially blinded to the exposure of losses.