c. notes – How A High-Performing Credit Union Upped Their Game

REDWOOD CREDIT UNION: A PROJECT MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY

This is the story of a highly successful organization that wanted to up their game. After taking a look in the mirror, they decided to change their approach to project management. Headquartered in the lovely town of Santa Rosa in Northern California, $3 billion plus Redwood Credit Union (RCU) always has lots of big initiatives in motion. At the time, they were converting a number of key systems, including the loan origination system, account opening system, phone system, and rolling out mobile deposit capture.

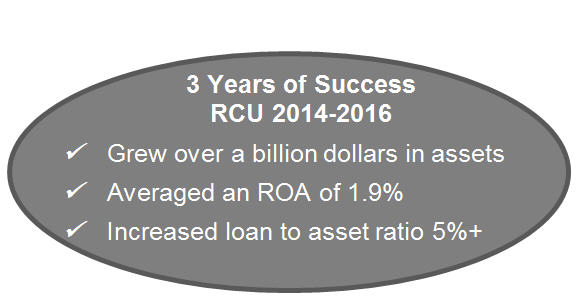

In the three years since completing their project management engagement with c. myers, the credit union has flourished.

In the three years since completing their project management engagement with c. myers, the credit union has flourished.

RCU’s vastly improved project management processes have stayed firmly in place, so we checked in to see what helped make them stick. But first, the backstory.

RCU recognized that the environment is changing swiftly and that those changes will not slow down. Remaining relevant in this highly competitive environment requires the ability to flawlessly execute on multiple high-stakes initiatives, nonstop. To that end, RCU asked c. myers to help address opportunities for improvement in project portfolio management and project management, ultimately landing on a series of customized processes that work for RCU’s structure.

Knowing that the ultimate objective was the ability to continuously execute well on multiple strategic projects, we got to work on identifying the friction points in project management. One that rose to the top was resource burnout. In reality, lots of projects were getting done, but in some cases there was a crunch to make it happen. In the organizations we work with, there is no single reason why resources become stretched too thin, so this issue was addressed from several angles. In the process, other friction points were addressed as the team honed in on the areas that made it possible to take project management to the next level.

The first big takeaway? Having a good process for managing the overall portfolio of projects is key.

DELIBERATE PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

Before focusing on project plans or project management tools, RCU needed to reach clarity on how projects should be initiated, vetted, prioritized, monitored, and closed out. It is this high level view that makes it possible to understand resource capacity and it is the process itself that defines the rules of engagement in project management. Case in point, it’s okay to say no to a project. This is an organization that is full of excited people who constantly push forward and are willing to take on a lot. There is a desire to say yes and who wants to discourage that? Of course, allowing too many projects to move forward reduces the likelihood that the right projects will get done at the right time. Well-placed no’s actually strengthen the organization and support the push forward.

We didn’t like to say no to projects. Now we have well-defined rules of engagement and a common language for handling project management – everyone now knows that “underground” projects are not okay.

We didn’t like to say no to projects. Now we have well-defined rules of engagement and a common language for handling project management – everyone now knows that “underground” projects are not okay.

– Cynthia Negri, EVP/COO

RCU had already partially rolled out a process for vetting and monitoring projects, which served as a base for ideas as they built their project portfolio management process. A Project Review Committee was created and was tasked with project portfolio management, including defining clear roles and specific processes for the committee to follow. The Project Review Committee is successful, in part, because the right people have visibility to the right projects. This sounds simple, but a great deal of thought went into defining the right people and the right projects.

JUST START – GETTING A HANDLE ON RESOURCES

This is a common sticking point because most organizations have an imperfect view of their available resources, but a perfect view is not required to greatly improve the situation. Becoming good at resource allocation is something that comes with practice, so it’s important to just start. Some of the simplest practices can begin to alleviate stress.

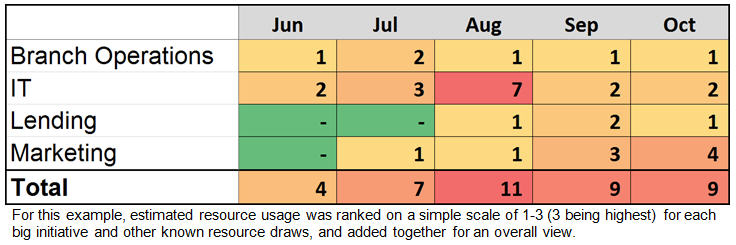

One example is staggering the scheduling of strategic initiatives. Many organizations start their big initiatives in the first quarter or have them all due at the end of the fourth quarter, but a good overall view of projects makes it possible to improve on the scheduling, which ultimately reduces resource burnout.

RCU started by mapping out the things that are no secret:

- Project planning time that is needed right after strategic planning

- Big IT updates (since IT is a resource for almost all projects)

- Busy times for departments

- Vacations for key individuals

This easily obtainable information was taken into account as projects were scheduled. Starting with broad-brush estimates of when departmental resources are required for different projects, then combining the projects and baseline information as a whole started them on the path of getting their arms around resources.

This example chart aggregates high-level resource usage estimates for big initiatives plus other known resource draws. The overall resource requirement rankings show IT over-allocated in August.

Overall Resource Requirement Rankings

(Selected departments only)

With this high-level view, project timing can be adjusted to relieve resource

over-allocation, before it happens, by shifting certain tasks to be done earlier or later, or even adjusting project due dates.

In our project management work, we often hear, we have too many projects. In reality, plenty of organizations do, but without at least a high-level idea of resource allocation, how do you know? This view, combined with carefully choosing and prioritizing projects, and saying no or not now to projects allows RCU to get more done – with higher quality, while reducing project stress and pain.

CLARITY – GETTING STAKEHOLDERS ON THE SAME PAGE

It’s not that project stakeholders actively disagreed on issues; in fact, they generally thought they were already on the same page. As is often true, each person held unstated beliefs which they assumed were common understandings. For example, is a mobile app “launched” when all mobile users can access it, or are Android and Apple users phased in at different times? Will all loan types be part of the initial rollout of the loan origination system, or are there some types that will be considered for inclusion later? The watchword here is clarity, and clarity comes from systematically having structured conversations geared toward getting those assumptions out into the light of day.

It’s not that project stakeholders actively disagreed on issues; in fact, they generally thought they were already on the same page. As is often true, each person held unstated beliefs which they assumed were common understandings. For example, is a mobile app “launched” when all mobile users can access it, or are Android and Apple users phased in at different times? Will all loan types be part of the initial rollout of the loan origination system, or are there some types that will be considered for inclusion later? The watchword here is clarity, and clarity comes from systematically having structured conversations geared toward getting those assumptions out into the light of day.

Clarity started with formally defining roles for the business owner, project manager, team members, and other key stakeholders. These definitions include the functions and responsibilities of each role so there is no misunderstanding about who should be doing what. The definitions must also include how issues should be escalated, and who is ultimately responsible for roadblock removal. No project manager should have to take responsibility for situations outside of their control, as long as the project manager follows the process and escalates the issue to the proper authority.

Clarity was also greatly enhanced by delving into project details to ferret out assumptions by asking what was not part of the project. Having a well-defined scope at the outset is a necessary first step in avoiding the dreaded scope creep. Examples include getting a clear understanding of how electronic signatures and document imaging are affected by the project, and whether any changes in these areas are part of the project.

In the same vein, team members created clear working agreements for each project. Working agreements might include being seated at the meeting start time, or how and when team members will make the project manager aware of off-track tasks. Working agreements were also defined for effective project meeting structure and vendor meeting structure. One thing that was helpful here was starting the project team meeting 30 minutes before the vendor meeting so the team could be fully organized before the vendor joined. They also extended the meeting past the time when the vendor signed off so meeting documentation could be completed and any new tasks assigned.

Setting and agreeing on clear expectations doesn’t guarantee accountability, but it certainly sets the stage for it.

NO NEWS IS NOT GOOD NEWS

When applied to projects, the old adage, no news is good news, tends to lead to unpleasant surprises. Good project communication prevents surprises and has some additional benefits that might not be as obvious. RCU chose a format for regular status updates to stakeholders that is easy to deliver and understand. It includes a condensed view of project status and pertinent details on outstanding issues, accomplishments, and current tasks. It also includes the project objective which helps to keep everyone focused on the bigger picture, even while they are knee-deep in tasks.

The obvious benefit is that stakeholders receive a regular update that gives them a quick, at-a-glance view of the project. To produce these regular updates, working agreements were created for how and when team members would provide status updates on their tasks to the project manager. This is where the less obvious benefits come into play. Individual team members were motivated to provide their updates timely because, if they didn’t, they risked having their tasks reported to all stakeholders as off-track. This prevented the project manager from having to chase down individual team members. Also, the act of creating the update required the project manager to make sure the project plan was up-to-date and to spend some time on the bigger picture view.

But there’s another factor that deserves mentioning here. No matter how diligent the updates, every project requires engaged stakeholders who will ask tough questions for the sake of clarity and uncovering hidden issues. Don’t go on autopilot just because a task or a project is deemed “on track” in an update. We find that the definition of on track varies between individuals. For example, a task that is due tomorrow is often reported as on track, even though it would require heroic efforts to complete, simply because it isn’t due yet. The project manager should be digging deeper, but there is no substitute for an engaged business owner who will doggedly pursue those questions.

THREE YEARS LATER

Now that RCU has been practicing their improved project portfolio management and project management for three years, they find that they still do lots of projects but those projects run more smoothly, are done with more quality, and there is less cleanup that needs to be done at the end. It still requires discipline to follow the process, but that discipline is habit now and the payoff is enormous. They sometimes overcommit, but far less than before, and they always consult their high-level view of resource capacity before saying yes to a project.

It’s OK to not be perfect, especially in the beginning

Have a little blind faith – follow the process and the gains will come

– Cynthia Negri, EVP/COO

On reflection, RCU identified these keys to success in creating their new organizational habits and making them stick:

- Buy-in. Buy-in is essential – especially at the top. In this case, the CEO was behind the project management initiative all the way

- Project Portfolio Management. Creating the structure for the Project Review Committee so the right people have visibility to the right projects, prioritizing projects and saying no or not now when necessary

- Discipline. Discipline in following all the steps of the project management process, especially in the beginning. It’s a continuous learning curve and tweaks to the process will be made along the way, so it’s okay if it’s not perfect at the start

- Clarity. Following a process that demands clarity on stakeholder roles, meeting structure, project communication, and working agreements

- Practice, practice, practice. It’s not easy to change behaviors on a large scale quickly. It takes focus, consistent correction, and a few repetitions before new organizational habits can be created

In the end, a successful organization that was doing a lot of things right found ways to get more done, and improved the member and employee experience at the same time. The first step was making a choice to devote the brain power and resources to figure it out.

As a result, the credit union is able to deliver on initiatives faster, with higher quality, and with less strain on the organization. Knowing that big changes will keep coming at the industry, Redwood Credit Union made a conscious choice to position themselves to respond swiftly, strategically, and tactically, in order to remain relevant to its membership as our industry’s exciting future unfolds.

Every organization is different. This case study has focused on some of the specifics that helped RCU push their project portfolio management and project management to the next level. This was not intended to offer a comprehensive overview of all aspects of project management. We hope that you have found the learnings helpful.

ABOUT c. myers

We have partnered with credit unions since 1991. Our philosophy is based on helping our clients ask the right, and often tough, questions in order to create a solid foundation that links strategy with desired financial performance.

We have the experience of working with over 550 credit unions, including 50% of those over $1 billion in assets and about 25% over $100 million, facilitating more than 130 process improvement, project management, and strategic planning engagements each year, and providing A/LM, interest rate risk, liquidity, and budgeting services.