Why Are My Income Simulation Results so Strong in a Shock?

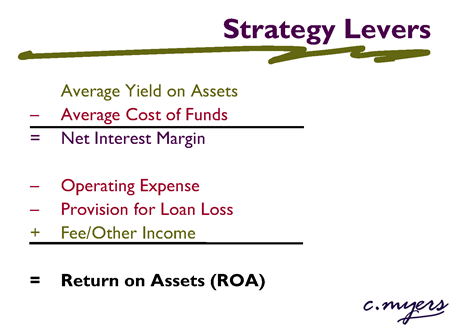

In performing model validations for credit unions, we often see income simulation results that show significant improvement in net interest income (NII) and net income (NI) as rates rise, even for credit unions that have material positions in long-term, fixed-rate assets. Why does this happen, and is it reasonable?

- What if our deposit mix becomes more heavily weighted toward member CDs as rates rise? In the largest credit union peer group, the last time rates went up, Reg Shares+Share Drafts dropped from 43% of funds to 33%; currently the ratio is 45%. When rates were higher, CDs were the largest deposit type, costing credit unions much more than non-maturity deposits. Does your base analysis incorporate members shifting funds like they did in the past?

- What if loan yields don’t move at 100% of the market? Competition to generate loans can often lead to irrational pricing. It is reasonable to expect that competition for loans may restrict the ability for institutions to move loan rates up 100% of the rate change.

- What if our loan-to-asset ratio is pressured as rates rise? Rates don’t only go up due to a thriving economy; the material drop in loan-to-asset ratios over the last five years has squeezed margins. Lending has picked up over the last year, but there is no guarantee that loan-to-asset ratios can’t drop again.