30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgages vs. 5/5 ARMs

Recently, we’ve seen more credit unions offering a 5/5 ARM product. While there are some differences institution-to-institution, usually the 5/5 ARM repricing characteristics have a 2% initial cap, a 2% annual cap and a lifetime maximum rate adjustment of 5% above the initial interest rate. The intent is to offer a product that is beneficial for the member by having a lower initial rate and smaller rate adjustments throughout the life of the loan due to the initial cap. As a side benefit, 5/5 ARMs are assumed to have less risk than a 30-year mortgage in a rising rate environment.

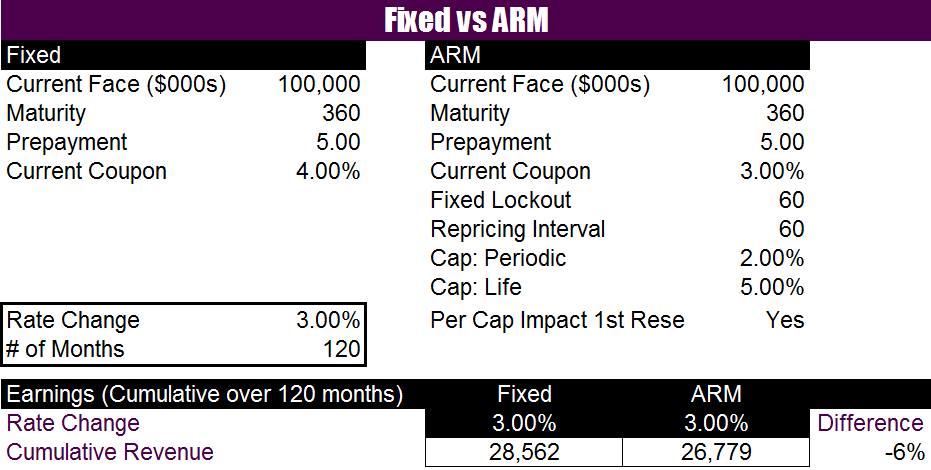

Let’s evaluate the 30-year mortgages and 5/5 ARMs from a business perspective over a 10-year period. The example below compares the earnings of a 30-year mortgage with a 4% rate to a 5/5 ARM with a 3% rate and the repricing characteristics described above in a +300 rate environment.

Over the course of 10 years, the 5/5 ARMs will not earn as much as the 30-year fixed mortgage. The 5/5 ARMs will certainly earn more in years 6 through 10 due to the higher rate, but that is not enough to offset the first 5 years of lower income compared to the 30-year mortgage. Eventually, the 5/5 ARMs will earn more than the 30-year mortgages; however, the breakeven point is not until about 12.5 years.

The 5/5 ARMs can be an additional product to offer members as a giveback. The key is to understand the trade-offs of such a product and how it fits with the credit union’s strategy.