Borrowing Trends are Changing…

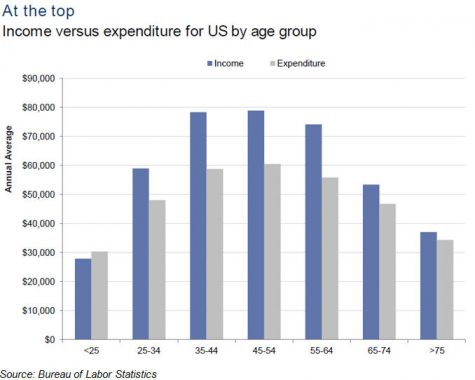

Would you be surprised by who is actually borrowing from your credit union, or applying for loans? A recent article in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) noted the growing trend of baby boomers moving into their retirement years completely unprepared from a financial perspective.

The article states that “people in the U.S. ages 65 to 74 hold more than five times the borrowing obligations Americans their age held two decades ago.” In addition, median savings has decreased 32% in the last 10 years for those people nearest retirement age. The result is that many Americans who should be enjoying retirement will work longer in life, and continue to borrow.

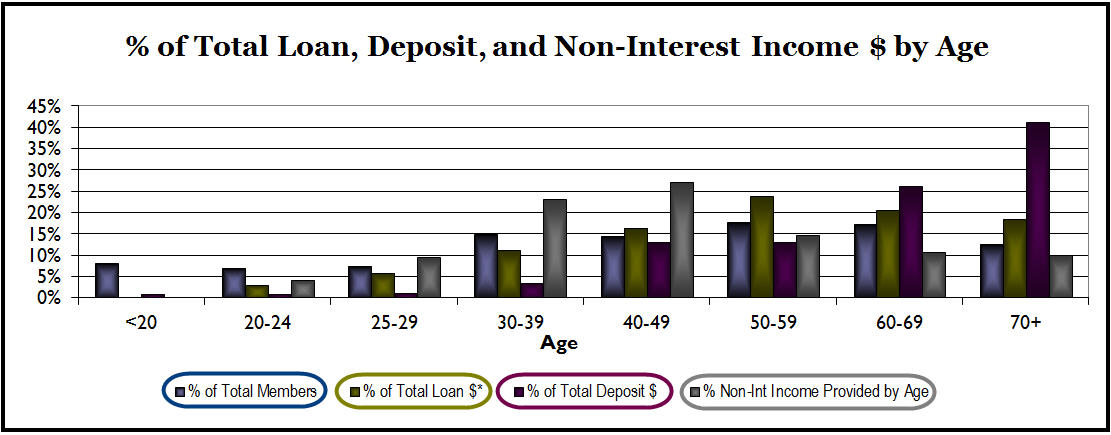

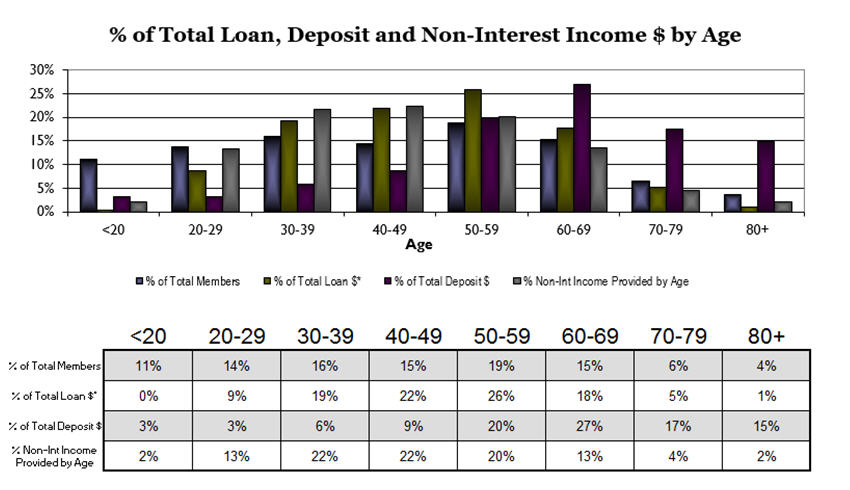

C. myers facilitates over 130 strategy sessions per year, and the data collected from those sessions lines up with the observations noted in the WSJ article. The image below is sample member demographic data for a credit union with more than $1 billion in assets as of June 2016.

If you focus on the two middle columns within each age bracket (loans and deposits) a couple of things stand out. The data shows that while members over the age of 60 do hold about 67% of this credit union’s deposits, that same age demographic also holds about 40% of the credit union’s total loans. This was a big surprise to this particular credit union. They had not realized that their loan portfolio was that skewed toward these age segments. This uncovered the possibilities of additional opportunities and considerations.

If Americans who traditionally would have been in their retirement years continue to remain in the workforce and remain active borrowers, what can this mean for your credit union? A few questions to consider include:

- How well do you know your numbers? For example, what percent of loan dollars are held by each relevant age segment? How many new loans have been generated by these age groups in the last 1-3 years?

- How do you determine if your credit union has a good handle on the needs and wants of the 60 and up age segment of your membership?

- What unique credit risk characteristics, if any, need to be considered?

- What does your credit union do to specifically market loans to this group?

Many credit unions are surprised to learn that this age group contributes so significantly to the credit union. As a result, they have put less effort or resources into cultivating these opportunities. For many, this discovery represents a chance to not only grow loans, but better serve this segment of the market. Is your credit union ready to capitalize on the changing needs and wants of this generation?