Strategic Questions around Indirect Auto Lending and Member Growth

How does your credit union define success when it comes to growth? For some credit unions it might be asset growth, growth in loans, or growth in membership. If one of your credit union’s key strategic objectives is growing membership, having the business intelligence to understand where new members are coming from becomes important. This blog will focus on strategic questions to consider regarding the impact of new member growth through indirect channels.

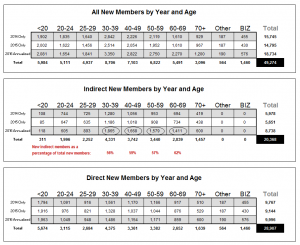

For many credit unions, a large percentage of membership growth in recent years has been driven by indirect members. The credit union demographic data noted below shows that between ages 30-70, the years when members do most of their borrowing, more than 50% of the total growth in members in 2016 came through the indirect channel (see the highlighted line in the second table). This information is noteworthy because this credit union has a strategic objective of deepening relationships with members as measured by products per member, and growth in indirect members may be at odds with that objective.

Growing indirect members is not necessarily a bad thing – in many ways the growth can be positive if the growth in members (and therefore loans) is managed appropriately. The key is to answer strategic questions and gain clarity on how indirect member growth impacts the credit union and its metrics.

Some strategic questions to consider:

- How does growth in indirect members impact metrics such as products per member, and is growth from indirect members segregated appropriately when looking at metrics? Increasing products per member would be significantly impacted by a majority of new member growth coming through the indirect channel.

- How do new indirect members fit within the description of the credit union’s desired target market(s)?

- How does indirect member growth support the long-term sustainability and strategy of the credit union?

- What is the credit union doing to market other products to the indirect members, and has it been effective?

- How many hours and dollars are spent trying to get those new indirect members to do additional business with the credit union? Can you quantify if those investments are paying off?

- How many indirect loans are actually made to current members versus non-members?

- If the credit union slows indirect growth for strategic reasons, or if auto sales slow, how will that be accounted for with respect to goals of membership growth, products per member, or other metrics?

- How does fast growth in indirect auto loans impact cross-selling opportunities with indirect members, or with the rest of the membership?

- Does indirect member growth create a false sense of security in metrics such as membership growth or loan growth?

Test driving some of the asset/liability management implications can be a good exercise as well. For example, if your credit union is heavily reliant on indirect auto lending to sustain the business model, imagine a scenario where market rates for deposits begin to rise. If your credit union has to increase deposit rates in order to maintain liquidity, can rates on indirect autos be increased enough to maintain margins given the competition for indirect lending in your market(s)? If not, how is the lost income replaced?

Having appropriate business intelligence in place can help alleviate some of the strategic challenges that rapid indirect member growth can create. Be clear in how you count new members and how your credit union could manage through a changing indirect auto environment. This can help ensure the credit union remains relevant and sustainable over the long term.