What-If Analysis In The Decision-Making Process – Test Your Hypothesis

Performing what-if analysis is an integral part of both the A/LM and budget processes. When used correctly, what-if analysis is a powerful way for decision-makers to understand the impact of items under consideration in real-time. The challenge is that often people dive right into modeling and results, producing a less than optimal process. Consider applying a scientific method to the what-if analysis to help strengthen the decision-making process.

The scientific method is essentially a hypothesis-driven methodology. Strong hypotheses lead to expectations either supported or refuted by analysis. What does this all mean? Well, it isn’t as intimidating as it might sound. From a financial modeling perspective, it means don’t just blindly rely on model results.

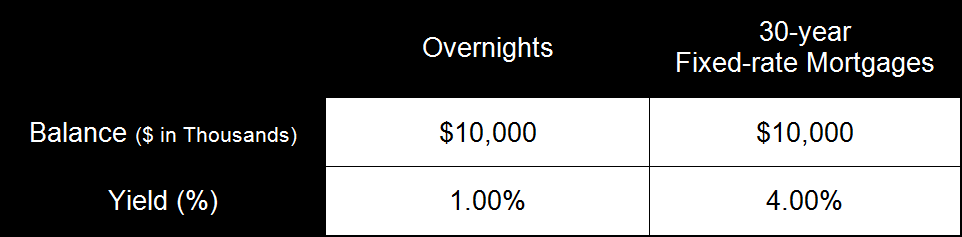

To help explain this concept further, consider a $1B credit union evaluating a strategy of moving $10M from overnights into 30-year fixed-rate mortgages:

Before performing a what-if, the scientific method suggests that you first ask what you expect the results to look like, and then create a hypothesis. Start broadly with what you generally expect to happen to earnings in the current rate environment and the risk. In this case, the shift from overnights to mortgages should help earnings in today’s rate environment, adding risk as rates rise.

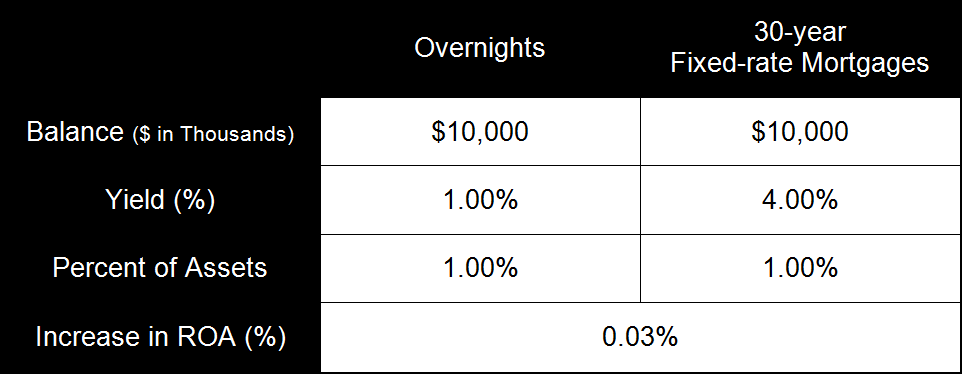

After identifying the broad expectation, take the next step and do some rough math to estimate the return on assets (ROA) impact of the what-if. Here, a $1B institution testing a strategy of moving 1.00% of its assets could expect a 3-basis-point improvement in the initial ROA (1% of assets multiplied by a 3% increase in yield):

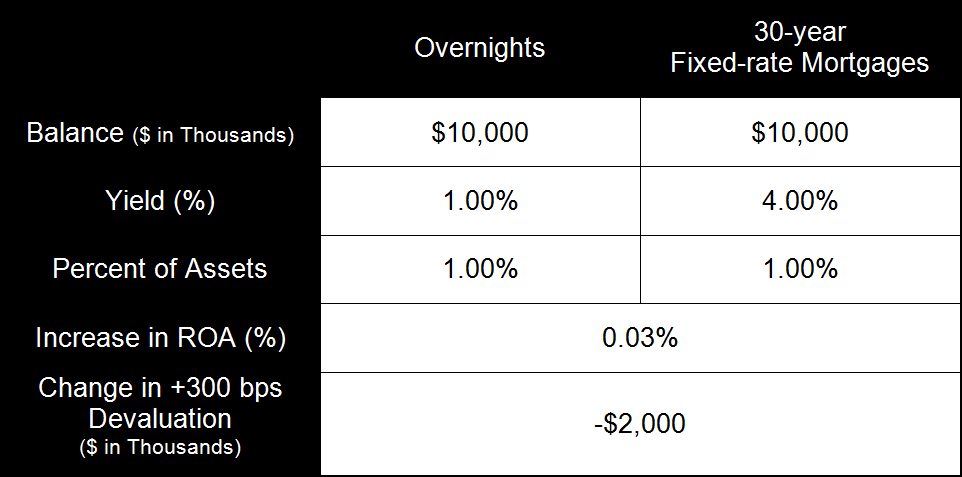

On the risk side, you can do the same with the impact to the net economic value (NEV) dollars since understanding the valuation impact is relatively straightforward. Overnights are at par in all rate environments while brand new 30-year mortgages devalue about 20% in a +300 basis points (bps) rate environment. Therefore, you’d expect to see a roughly $2M decrease in your NEV dollars in the +300 bps rate environment:

Analysis and observation are the next important steps in the scientific method. Run the what-if through the model and analyze the results in comparison to your expectation and rough math. Do the results of the what-if validate the hypothesis and, if not, why?

Periodically, results may not match up with the hypothesis, which is okay. It doesn’t necessarily mean the model or the hypothesis is incorrect. There could be other factors impacting the what-if. However, it is important to figure out why the results do not match up, especially if the difference is due to an input error.

For the example above, consider some of the following questions that could affect the what-if, causing the hypothesis and results not to match:

- What was the credit risk assumption?

- Will additional operating expenses and/or marketing dollars be needed to attract the growth?

- Did we incorporate any fee income for the closing costs?

- How long will it take to increase the portfolio $10M?

When it comes to the what-if process, shortcuts should not be taken. Always create an expectation internally before relying on model results. Depending exclusively on model results puts the user at risk of input errors and/or an inability to effectively explain what-if results.